![]()

![]()

Middle English Language

General Issues

- French influence

- Scandinavian influence

- loss of inflections

- less free in word order

- loss of grammatical gender

- final -e pronounced, as well as all consonants

- decline of English under French Norman rule

- resurgence of English in 14th century

- dialects: Northern, Midland, Southern, Kentish

- dominance of London dialect (East Midland); standard Modern English not a direct descendant of West Saxon but of the Middle English London dialect

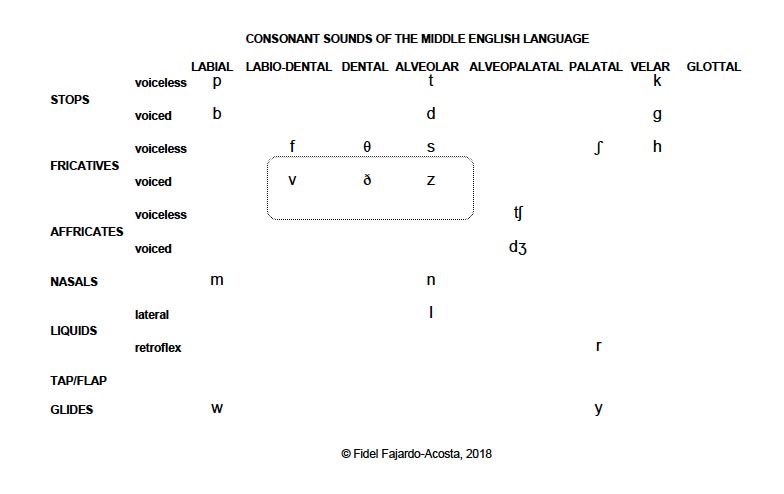

PhonologyConsonants

- consonants of Middle English very similar to those of Present Day English but lacking [ŋ] as in hung, and [ʒ] as in measure, as well as sounds like the flap [ɾ] and the glottal stop [ʔ]

- addition of phonemic voiced fricatives: [v], [ð], [z]; effect of French loanwords: vetch/fetch, view/few, vile/file (new sounds are circled in the chart below) :

- many simplifications of consonant sounds, e.g. loss of long consonants, consonants in clusters, final consonants:

- OE mann > ME man

- OE hlæfdige > ME ladi ("lady")

- OE hnecca > ME necke ("neck")

- OE hræfn > ME raven

- OE ic > ME i ("I")

- OE -lic > ME -ly (e.g. OE rihtlice > ME rihtly ("rightly")

- OE cuman > Modern English come (the n remains in some past participles of strong verbs: seen, gone, taken);

- OE min > ME mi ("my")

- OE sweostor > sister, (sometimes the [w] is retained in spelling: sword, two; sometimes still pronounced: swallow, twin, swim)

- OE ælc, swilc, hwilc, micel > each, such, which, much (sometimes the [l] remained: filch)

- OE hit > ME it

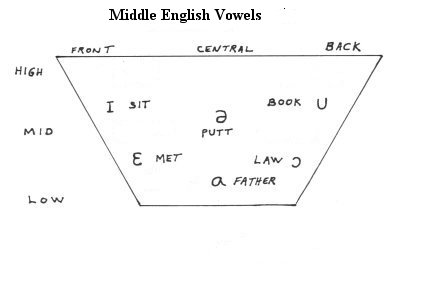

Vowels

vowels in Middle English were, overall, similar to those of Old English, except for the loss of OE y and æ so that y was unrounded to [I] and [æ] raised toward [ɛ] or lowered toward [ɑ].

addition of new phonemic sound (mid central vowel), represented in linguistics by the symbol called schwa: [ə], the schwa sound occurs in unstressed syllables and its appearance is related to the ultimate loss of most inflections

the Middle English vowels existed, as in Old English, in long and short varieties:

Some examples:

day [dai]

cause [kausə]

soule [sɔulə]

hous [hus]

fruit [fruit]

French loanwords added new diphthongs, e.g. Old French point, noyse, boillir, embuié > ME point, noise, boillen, boi ("point," "noise," "boil," "boy")

vowel length:

- vowels lengthenings:

- short vowels lengthened when they occurred in open syllables, i.e. when the syllable ended in a vowel: OE gatu, hopa, nama > ME gāte, hōpe, nāme ("gate," "hope," "name").

- in general, a vowel in a closed syllable (i.e. a syllable ending in consonant and followed by another consonant) shortened or stayed short: OE sōfte, scēaphirde > ME softe, scepherde ("soft,""shepherd"); but there were exceptions: OE gast, crist > ME gōst, Chrīst ("ghost," "Christ"); OE climban, feld > ME clīmbe, fēld ("climb," "field").

- in a long word (if two or more unstressed syllables followed the stressed one), the vowel of the stressed syllable was shortened: Christ (long vowel)/Christmas (short vowel)[ME Christesmesse], break (long vowel)/breakfast (short vowel)[ME brekefast]

- some remnants of distinctions caused by lengthening or shortening of vowels in open and closed syllables: five/fifteen, wise/wisdom; in weak verbs, the dental ending closed syllables: hide/hid, keep/kept, sleep/slept, hear/heard

Middle English Prosody

stress on root syllables, less stress on subsequent syllables

loss of endings led to reduction in number of unstressed syllables, increased use of unstressed particles such as definite and indefinite articles, prepositions, conjunctions, pronouns, analytic possessive (of), marked infinitive (to), compound verb phrases

OE trochaic rhythm shift to ME iambic rhythm (unstressed syllables followed by stressed ones) (caused by increase in use of unstressed particles and by French loan words accented at the end of the word)

Middle English Graphics & Writing

Not much English writing during 1100-1200 period; influence of French scribes; new spelling conventions

ash (æ) and eth (ð) dropped, thorn (þ) and yogh (ʒ) retained; French loans "j" and "v" treated as allographs of "i" and "u"; interchangeable "y" and "i"

yogh: ʒ -- a Middle English character derived from the Old English character for "g"; it had various pronounciations, ʒelden ([y], "yield"), cniʒt ([h], "knight"); þurʒ, ([h], "through"), bridʒe ([dʒ], "bridge"), dayʒ ([s], "days")

"q" and "z" more widely used under French influence, "qu" for /kw/ OE cwic, cwen > ME quicke, quene

confusion of y and þ, (this is the origin of the erroneous expression "ye olde coffee shoppe")

o for u (words like come, love, son, won, tongue, some were all originally spelled with "u"), the spelling was changed to "o" to avoid confusion caused by use of minims (vertical strokes in certain styles of manuscript writing)

final -e after a single consonant indicated that the root vowel was long: OE fōda > ME fōde ("food"); OE fēdan > ME fēde ("to feed") -- cf. OE hūs > ME hous > Mod. Eng. house

increased use of digraphs:

- th for thorn/eth

- ou/ow for long u (hour, round)

- doubling of vowels to indicate length (beet, boot, good)

- sh for [ ʃ ] (OE scamu > shame)

- ch for [ tʃ ] (OE ceap, cinn> ME cheap, chin)

- dg for palatal affricate [ ʃ ] (OE bricg > ME bridge)

- gh for [h] (OE þoht, riht> ME thought, right

- wh for hw, OE hwæt, hwil, > ME what, while

punctuation: question mark; hyphen for word division at end of line; paragraph markers

handwriting: Insular hand replaced by Carolingian minuscule script

Middle English Morphology

- loss of inflections

- loss of grammatical gender

- two noun cases: possessive and non-possessive

- all adjective inflections lost, loss of weak/strong distinction

- verbs: personal endings reduced, mood distinctions blurred

- dual/plural distinction lost

- change from synthetic to analytic language due to loss of inflections, reduction of unstressed final vowels, interaction of different grammatical systems in English, French, and Scandinavian

- relative rigidity of word order, increasing use of prepositions and particles

- changes more visible in north of England where reduction of inflections began

Nouns

noun class distinctions disappeared

-es for genitive singular and all plurals:

Number Case Old English Middle English Singular Nominative bāt ("boat") bāt Accusative bāt bāt Genitive bātes bātes Dative bāte bāt Plural Nominative bātas bātes Accusative bātas bātes Genitive bāta bātes Dative bātum bātes weak declension endings (-n) survived into early ME then merged with strong declension (some survivals: children, brethren, oxen); some ME words had plurals with -n: eyen, earen, shoen, handen

some unmarked plurals: some OE strong neuter nouns had no ending in the nominative and accusative plural, continued in ME (year, thing, winter, word); unmarked plurals for animal names (derived from OE unmarked neuter plurals, e.g. deer); measure words without -s in the plural (mile, pound, fathom, pair, score), derived perhaps from s-less plurals of year and winter

Adjectives

greatest inflectional losses; totally uninflected by end of ME period; loss of case, gender, and number distinctions

distinction strong/weak lost; causes in loss of unstressed endings, rising use of definite and indefinite articles

comparative OE -ra > ME -re, then -er (by metathesis), superlative OE -ost, -est > ME -est; beginnings of periphrastic comparison (French influence): swetter/more swete, more swetter, moste clennest; more and moste used as intensifiers

Personal Pronouns

preservation of gender, number, case, and person categories; merger of dative and accusative into single object case; dual number disappeared

Number Case 1st Person 2nd Person 3rd Person m. 3rd Person n. 3rd Person f. Singular Nominative ic, I ("I") þu, thou ("you") he ("he") hit, it ("it") heo, sche ("she") Accusative/Dative me þe, thee him hit, it hire, her Genitive min, mi þin, thin his his hire, her Plural Nominative we ʒe, ge, ye hi(e), þei hi(e), þei hi(e), þei Accusative/Dative us ʒou, you hem, þem hem, þem hem, þem Genitive ure, our ʒur, your here, þair here, þair here, þair use of 2nd person plural (ye) to address one person as polite form (French influence), eventual loss of singular forms in 18th c.

First-person singular: ich/I; loss of unstressed final consonant led to first person singular form I (pronounced as the 'i' in "kid");

feminine third person singular, heo/sche, -- [š] appeared first in North and East Midlands and allowed distinction from masculine forms

Third person plural, he, hem, here; then borrowing of pronouns from Old Norse (nom. þeir, dat. þeim, gen. þeira> they, them, their) to prevent confusion with other forms, especially in the singular and feminine

Verbs

ME retained categories of tense, mood, number, person, strong, weak and other verbs

added new type of verb, two-part or separable verbal expression (e.g. put in, blow out, pick up, take over) (cf. Old English ingangan ("to go in"), oferniman ("to take over")

increased use of weak verbs

Weak Verb Strong Verb Infinitive lok(e) "to look " find(e) "to find " Present Tense Indicative Mood 1st person singular loke finde 2nd person singular lokest findest 3rd person singular lokeþ, lokes findeþ, findes 1st person plural loke(s,n) finde(s,n) 2nd person plural loke(s,n) finde(s,n) 3rd person plural loke(s,n) finde(s,n) Subjunctive Mood singular loke finde plural lok(en) finden Imperative Mood 2nd person singular lok find 2nd person plural lokeþ, lokes findeþ Present Participle loking finding Past (Preterite) Tense Indicative Mood 1st person singular loked fand 2nd person singular loked(est) fand 3rd person singular loked fand 1st person plural loked fand 2nd person plural loked fand 3rd person plural loked fand Subjunctive Mood singular loked fand plural loked fand Past Participle loked funden

Interjections: a, surprise; ho, triumph; ha-ha, laughter; fie, disgust; hay, excitement; lo, now, what: attention getters; alas, wo, wei-la-wei, grief; hail, welcome, salutations; others: good morrow, good night, farewell, gramercy (French: grant merci), thank you, benedicite, goddamn, bigot (by God)

Middle English Syntax

- adjective before noun (erthely servaunt)

- articles: indefinite article (a/an) derived from numeral "one"

- isolated possessive marker (the raven is neste)

- analytic possessive (of) (a parallel to the use in French of possessive "de")

- "the King's castle of England" = the King of England's castle

- double possessive (obligacion of myn)

- negative ne before verb (I nolde fange = I ne wolde fange)

- double negatives freely used

- prepositions before objects; sometimes followed if object was pronoun (he seyde him to)

verb phrases: origin of compound verb phrases; perfect tense became common, use of auxiliaries (be & have); progressive tense came into being; passive constructions (with 'be' as auxiliary); future tense (with shall and will auxiliaries); modal auxiliaries instead of subjunctive (may, might, be going to, be about to); do in periphrastic constructions indicating tense (doth serve, did serve);

impersonal verbs and dummy subjects: me thristed, hit me likede (cf. methinks)

trend toward modern word order: SVO in affirmative independent clauses; VSO in questions and imperatives

Middle English Lexicon

large lexicon; assimilation of loanwords; variety of vocabulary levels; cosmopolitan language; about 10,000 words borrowed from French

loans:

- French:. prince, princess, justice, empire, noble, baron, dame, servant, uncle, cousin, dinner, supper, government, crown, state, estate, tax, traitor, minister, university, attorney, judgment, chivalry, fashion, dress, passion, religion, enemy, hello, please

- Scandinavian (Norse): they/them/their, anger, egg, husband, bull, skin, sky, skill, mistake, weak, awkward, reindeer, steak

- Latin: apocalypse, purgatory, testament, comprehend, lunatic, temporal

vocabulary losses: much of OE vocabulary lost during ME period (e.g. OE earm replaced by French poor); cultural and technological change; obsolescence

Middle English Semantics

Some examples of semantic change:

- pejoration (OE ceorl ('peasant') > ME cherl, "churl")

- amelioration: dizzy (meant 'foolish' in OE)

- amelioration: the French borrowing nice ('foolish', 'stupid'; derived from Latin nescius "ignorant") acquired more positive meanings (flamboyant, rare, modest, elegant) in 15th century

- weakening (OE ege (terror) > ME awe ('reverence' 'respect')

- shift in denotation: OE cniht ('boy')> ME knight ('young gentleman soldier')

Middle English Dialects

dialects: Northern, East Midlands, West Midlands, Southern, Kentish

Middle English Samples:

From the General Prologue of Chaucer's Canterbury Tales (c. 1400) (East Midlands, London dialect):

1: Whan that aprill with his shoures soote

2: The droghte of march hath perced to the roote,

3: And bathed every veyne in swich licour

4: Of which vertu engendred is the flour;

5: Whan zephirus eek with his sweete breeth

6: Inspired hath in every holt and heeth

7: Tendre croppes, and the yonge sonne

8: Hath in the ram his halve cours yronne,

9: And smale foweles maken melodye,

10: That slepen al the nyght with open ye

11: (so priketh hem nature in hir corages);

12: Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages,

13: And palmeres for to seken straunge strondes,

14: To ferne halwes, kowthe in sondry londes;

15: And specially from every shires ende

16: Of engelond to caunterbury they wende,

17: The hooly blisful martir for to seke,

18: That hem hath holpen whan that they were seeke.

First stanza of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (c. 1400) (Northwest Midlands dialect):

1 siþen þe sege and þe assaut watz sesed at troye

2 þe borʒ brittened and brent to brondez and askez

3 þe tulk þat þe trammes of tresoun þer wroʒt

4 watz tried for his tricherie þe trewest on erþe

5 hit watz ennias þe athel and his highe kynde

6 þat siþen depreced prouinces and patrounes bicome

7 welneʒe of al þe wele in þe west iles

8 fro riche romulus to rome ricchis hym swyþe

9 with gret bobbaunce þat burʒe he biges vpon fyrst

10 and neuenes hit his aune nome as hit now hat

11 ticius to tuskan and teldes bigynnes

12 langaberde in lumbardie lyftes vp homes

13 and fer ouer þe french flod felix brutus

14 on mony bonkkes ful brode bretayn he settez

15 wyth wynne

16 where werre and wrake and wonder

17 bi syþez hatz wont þerinne

18 and oft boþe blysse and blunder

19 ful skete hatz skyfted synneTranslation: After the siege and the assault of Troy, when the city was burned to ashes, the knight who therein wrought treason was tried for his treachery and was found to be the truest on earth. Aeneas the noble it was, and his high kindred, who vanquished great nations and became the rulers of wellnigh all the western world. Noble Romulus went to Rome with great show of strength, and built that city at the first, and gave it his own name, as it is called to this day. Ticius went into Tuscany and began to set up habitations, and Langobard made his home in Lombardy; whilst Brutus, far over the French sea by many a full broad hill-side, the fair land of Britain [bob] did win, [wheel] Where war and wrack and wonder/Often were seen therein,/And oft both bliss and blunder/Have come about through sin.

Recommended texts:

Celia M. Millward, A Biography of the English Language (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1988)

Albert C. Baugh & Thomas Cable, A History of the English Languag, (Prentice Hall, 2002)

Thomas Pyles & John Algeo, The Origins and Development of the English Language (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1993)

© 2000-2018 by Fidel Fajardo-Acosta, all rights reserved

Last updated: November 27, 2018 23:32